Take the risk and the chance to be imaginative in a way that is unexpected… Just do it. Really, that’s the only way you’re going to discover whether something is appropriate or not appropriate, whether something is able to hold and sustain that vision or not and it’s only through doing it and making mistakes that I think you’ll know more …

Richard Lee, Sound Designer

Interview, June 6, 2016

Staging of ASL Interpreters

Interpreting tips include notes from Tara Everett, Interpreter, ULTRASOUND

First your company needs to consider why you wish to engage interpreters. What is your company’s goal and artistic vision in engaging interpreters for your production? Are you casting Deaf actors in the production? Are you seeking to make a spoken language performance accessible to both Deaf and hearing audiences? Your vision will help determine whether you will engage hearing and/or Deaf Interpreters, if interpreters are required throughout the duration of the rehearsal and performance process or for a few rehearsals and select performances, and how you will stage the interpreters – to be zoned or shadow interpreters for different productions or for different performances in a given production.

Zoned Interpreting – the interpreter is blocked by the Director to interpret within a specific location onstage. The interpreter can move from one allocated zone to another zone, but usually moves only during a change of scene or act, or for a specific event in a performance for dramatic effect. More than one interpreter can be used in zone interpreting. In such cases, interpreters can be located in more than one zone (one interpreter per zone) and would interpret actors as they approach their interpreting zone. Lighting of these zones is crucial for audiences to be able to clearly see the signing of the performance.

Shadow Interpreting – the interpreter is blocked by the Director to move freely onstage shadowing the movement of the actor(s). More than one interpreter can be used to shadow different actors as they interact with one another.

Hearing Interpreters or Deaf Interpreters can be hired for zoned or shadow interpreted performances. Hearing interpreters are hired to be on stage for the Deaf audience experience or for the Deaf and hearing audience.

Deaf interpreter(s) (DI) are hired to be on stage for the Deaf audience experience – The DI may work in a team with (a) hearing interpreter(s) if the DI is not “off book”. In the instance of Ultrasound, the Hearing interpreters were situated in house seats facing the stage to interpret spoken English presented on stage into ASL for the DI on stage. The DI then incorporated ASL and cultural knowledge in their interpretation with appropriate regional variation and level from a Deaf experience perspective for the Deaf audience. Some theatre companies in the U.S. use the term “shadow interpreter” instead of “DI” for that role. However, a DI can be staged in one zone or a few zones, or staged as a shadow interpreter.

Speaking actor → Interpreter in house seats → Deaf Interpreter (DI) on stage → Deaf audience

The hearing interpreters in the house seats also provide stage cues to the DI regarding zone location to indicate when to move from one zone to another.

Other methods of interpreter set-up and support are possible. For instance, if there is not an ideal placement for the hearing interpreters in the audience, then a monitor could be set up onstage for the DI, with a feed from the hearing interpreters who could be situated in the wings or in the booth alongside the stage manager.

Ideally, the DI would rehearse right from the beginning in order to be “off book” in which case the DI would not need hearing interpreters to be in house seats providing cues.

Speaking actor → Deaf Interpreter (DI) on stage → Deaf audience

For Ultrasound, we decided to have a Deaf interpreter on stage as the character that was represented onstage was a Deaf character with a beginner level of ASL and it felt in keeping with this character.

A Deaf interpreter may also be selected for shadow interpreting. Considerations to select a hearing ASL/English interpreter or Deaf interpreter for a specific performance includes the artistic vision of the specific performance and can be discussed in consultation with a Deaf Community Consultant.

Tips for Interpreted Performances:

- Bring in Deaf expertise from the start including an ASL coach for the interpreters and Deaf community consultant for the production as a whole.

- The Script must be translated to ASL. The director of the production needs to be involved from the beginning regarding artistic vision/goals and for division of script with interpreters.

- The lighting designer must be involved in designing and setting lighting levels for hearing interpreters in-house if they are situated there. Each theatre is different and so consultation with your Deaf community consultant to determine appropriate lighting levels in your specific in-house environment will also be important.

- Lighting in-house during, technical rehearsals, for DI on stage and/or for hearing interpreters on stage is essential for clear communication.

- Access to a video of the rehearsal for DI and/or hearing interpreters to work from is essential to determine and practice pace, consistency, set-up and blocking. If actors are with a union (in Canada, either Canadian Actors’ Equity Association [CAEA] or Union des Artistes [UdA]), permission must be granted to video the rehearsal for internal purposes only to be used during the rehearsal period only. It is helpful to not work off of the script alone.

- A person to share notes from the director to the interpreters is helpful for any rehearsals that interpreters are not in attendance for regarding tone and delivery as decided by director with actors. This could be done by the Deaf Community Consultant if the consultant is present in the rehearsal and if it is agreed in advance.

- Consistency of interpreters is important

- Interpreter flexibility is key during rehearsals while maintaining the parameters of the interpreter role. It is important not to impede the process, but also to speak up when necessary, balancing production process AND equal access.

- The sharing of information betweeninterpreters is important. Interpreters in the rehearsal hall must be aware of everything that is happening in the room and communicate that. For example, informing the Deaf actors if a minute is needed during tech week for a side conversation among designer/director, or to let the stage manager know if a minute is needed for the Deaf actor(s) so they are aware and they can move on.

-

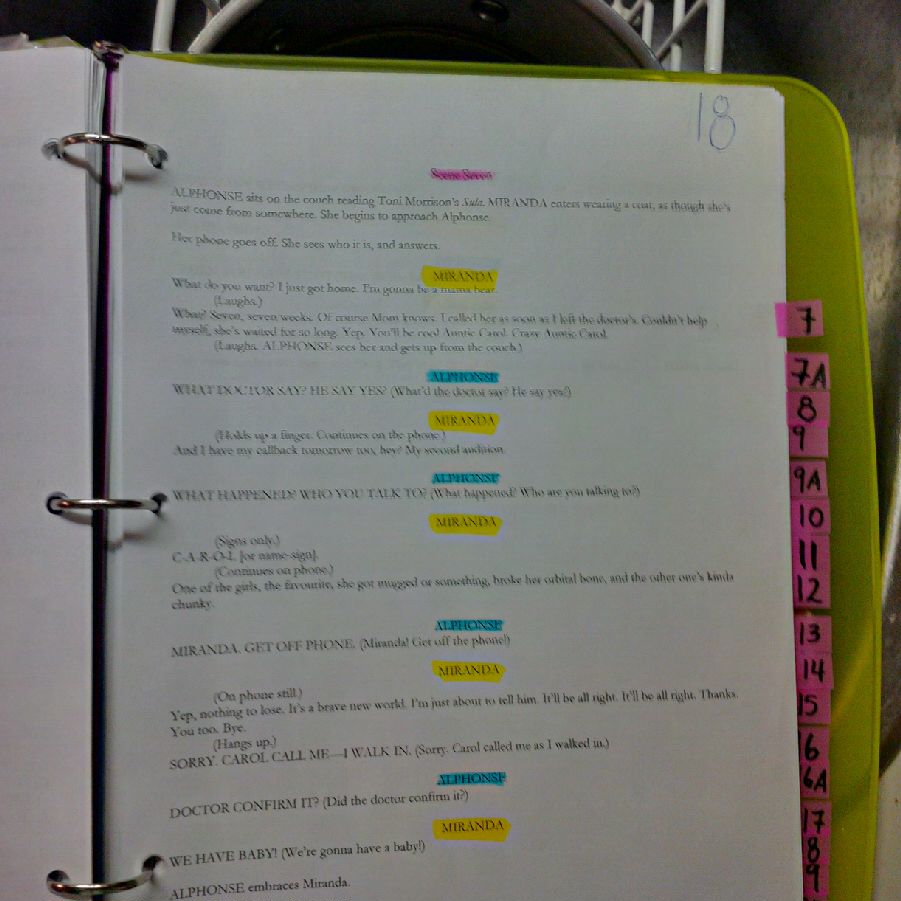

Interpreter script scene markings Stage notes in the script can be marked by the interpreters according to their preference. Some suggestions include: page numbers enlarged at the top, each character colour coded, beside the character’s name, indicate if it is speaking lines only or spoken lines only in brackets.

- It is critical to include the DI in rehearsals as early as possible, not mid rehearsal but right at the outset. We strongly encourage selecting the DI as close to cast selection as possible so they have time to determine translation, rehearse and be “off book”. Blocking happens on stage during rehearsal time. This is true for hearing interpreters as well. They should be hired early in the process along with the cast to provide time to read and translate the script, discuss interpretation with the artistic director as needed and to practice their interpretation off book, to eliminate lag time on stage and so they can practice matching the character(s) in the performance.

- It is The DI needs to rehearse with hearing interpreters in advance. It is most helpful to have two hearing interpreters (one signing for each actor if there are two actors) so the DI knows who to follow for his/her own role if s/he is only following one actor. S/he still needs to know what the other actor is saying and for the two roles to be clearly delineated by the hearing interpreters. This technique properly prompts the DI to know when to interpret his/her character’s lines.

Really trusting in this case, my director Marjorie Chan and her sense of how the room was going to work and the dynamic of who says what when and when is a goodtime to ask a question as a designer, when is a good time to jump up and work with an actor on a difficult prop … everything had to be done through a little bit of mediation … and that means a little bit more patience, more time with it, maybe there’s a way to work with it you haven’t yet figured out.

Trevor Schwellnus

Set, Lighting and Surtitle Designer

Interview, June 6, 2016

Integrated Design

Integrated design includes: costumes, set, projection, surtitles or dynamic titles, lighting, sound (subwoofers). Each production will have its own unique integrated design that speaks to the artistic vision while creating an engaging and empowering artistic experience for all. Universal design naturally becomes part of creating that vision. We have created a separate section for Interpreters, yet, ASL is part of universal design and decisions around interpreters is considered from the outset as part of the integrated artistic design of the production.

Costume Design[1]

Interpreters tend to dress in black or a plain solid colour with no pattern so as not to distract from the performance.

If an actor will be signing continuously for long periods as a solo performer some guidelines include the following:

- Avoid patterns as this might make it hard to read the signer’s hands.

- It is best if the signer’s skin tone contrasts with the clothing they are wearing (dark clothes for someone with light skin and vice versa, etc)

- Even a patterned tie or dangly necklace can distract from the signing if the actor is signing for a long period with no break.

- Ideally sleeves will end above the wrist and not be too full or flowy if they are long.

While these suggestions are important to be aware of, they are not hard and fast rules and should be considered in the artistic context of your particular performance.

Projection and Surtitles[2]

In ULTRASOUND, dynamic titles were used. These are surtitles that have no fixed surface throughout the production but rather are projected onto the set in a variety of areas in order to follow the characters movement on stage. It is important that the dynamic titling was placed closely to the actors; not up too high nor too far from the performers action on stage. So much visual information is provided through the actors’ bodies so it is important to maintain a visual relationship between both the performer and the dynamic surtitling provided.

A shallow stage is recommended if you want the body of the actors signing as close to the audience as possible and to bring the energy out to the audience. The other benefit is the sight lines. The deeper the stage is, the higher you have to place your surtitles so that the audience can see over the person’s head in front of them to read things on stage. Compressing the depth of the stage maintains consistency of the titles with the actors and simultaneously brings the energy out into the audience without barriers.

It is of great benefit to have a team working on surtitle interpretation. You need that legwork with the actors, interpreters and consultants because it is not a direct translation. The signs the actors choose to use effects the dynamic surtitle word choice and there’s no short cut around that – great team work and gentle consultation during the rehearsal process is needed.

A detailed example of the process of dynamic surtitles follows.

Dynamic Surtitles: A Step by Step Guide from “Surtitle Sally”

(Sally Roberts, Surtitles Operator, Ultrasound)

The beginning – choose your program

- Ultrasound used Keynote for Mac, a program which allows for editing with master slides. This is very important when it comes to placement of titles on the stage and allowing for efficient show wide edits.

- You could also use Microsoft PowerPoint or do some research into other software that is available.

Who is responsible?

- Surtitles will require a lot of attention. It is important for the company to budget accordingly and to discuss this responsibility with the production team. Decisions on who will be responsible for creating the file, keeping track of script changes, blocking notes if necessary, designing, and operating the surtitles during the show will need to be made. It is extremely useful to engage someone in this position who has some ASL as they will be dedicated to building/editing the titles during rehearsals and operating surtitles in response to the performers, who may be Deaf and signing their lines.

Copying the script

- Copying and pasting the script over from a word doc format into a line by line slide file is a way longer and more tedious process than you think. Make sure the person responsible for this task allocates the appropriate amount of time to complete this detailed entry.

- Do not make any edits to the text at this stage, unless edits or paraphrasing have been discussed and confirmed with the author.

Rehearsal

- It is important to budget and plan to incorporate using the surtitles during rehearsals. Ensure that the surtitles file is ready prior to the start of rehearsals. It is important that any changes made to the script during rehearsals are maintained in the surtitles file throughout this process. Additionally, blocking notes and surtitles placement can be included at this time, if dynamic surtitling is being implemented.

Production

- What is the surtitles design? Consider colour, font size and type, positioning, visual esthetic.

- What are you projecting the surtitles onto? Set design greatly influences the legibility of the surtitles. It is important that the designer considers the projection material. Will it be painted? Will there be multiple projection surfaces within the set design or is the whole set a surface?

- What kind of projector do you need? Consider the lumen count in selecting the projector required – brightness and range are important elements to factor in. How many projectors do you need? Where will the projector(s) be placed? Will it be rear projected or front projected? Is there a projection design in addition to the surtitles projection design and how does this influence things? How do they work together?

Tech week

- Map the surtitles to the place they are being projected onto. This can be done within your surtitles file program (Keynote), like in Ultrasound, or with external video software like Isadora.

- Using Keynote to map the titles is possible but also extremely time consuming. Find the pixel height and width of the projection area and build master slides to be like focus points. For example: Surface A is 379 pt high by 679 pt wide and located at X 0 pt and Y 36 pt on the screen, create a master slide called “Surface A” with the text box at that dimension and it will always land in the same place. It is all trial and error until it works. Then it’s as easy as applying your master slides to your lines of text.

- What are the sight lines like in the theatre? Can everyone see the titling in all the positions from all the seats?

- Are the titles still visible in the lighting states being built?

- Where is the surtitles operator sitting? Do they have a clear line of sight to the stage and the actors and especially for ASL?

Interview with Sally Roberts, Associate Production Manager & Surtitles Operator, ULTRASOUND

Lighting

- With a mesh or scrim-like material, high side lights safe guard against light bouncing off the back wall and washing out the text in the dynamic titling.

- It is important to have quality lighting from a variety of angles on the performers and interpreters to see their facial expressions as well as their signing.

- Backstage lighting for the actors is important in order for them to feel comfortable with tracking their backstage paths during the performance.

-

Photo Credit: Dahlia Katz It is important to consider how movement works and to take into account that Deaf actors likely need to communicate backstage, have quick changes that requires backstage sign language communication, so it is best to provide some light for this which may be brighter than you are accustomed to.

- It is important to incorporate lighting placement and levels during tech week for the interpreted performances. You do not want to be stuck last minute having to add lights – you can anticipate those positions and have dedicated lights. A performance with a DI has hearing interpreters in the house seating for the DI to see, so it is critical to have a light on them so the DI does not have to strain to see them. It is difficult to determine precisely where the hearing interpreters will need to sit until getting into the performance venue so this will need to be finalized during tech week.

Trevor Schwellnus, Set, Lighting & Surtitles Designer, ULTRASOUND

Sound Design

The sound designer can wear a sound cancelling device to explore experiencing the play as a Deaf audience member might. Ultrasound is an example of a production that has entryways for both hearing and Deaf audiences. The sound choices were made with this in mind and the intent to carry the story powerfully and to take any audience member along the same path. For instance, sub-woofers were placed under house seats reserved for Deaf audiences to provide the bass reverberations to Deaf audience members during a storm sequence.

Lighting cues and sub-woofers can be used for actors as the context for sound. The sound designer was cognizant not to get caught up in gimmicks that intentionally make sound visible (like coloured lights, etc. that are flashy) but may distract from the story as it unfolds. Rather, the desire is to find a way that moves the story forward and that connects with the whole audience as it maintains the integrity of the story told.

It is encouraged, to invite some Deaf patrons to attend a dress rehearsal or preview to provide feedback on the hearing assist devices and respond to the production during a period of the process that allows for changes to be applied.

Interview with Richard Lee, Sound Designer

ASL and Vocal Coaching

ASL Coaching

-

Photo Credit: Dahlia Katz. (L-R) Marjorie Chan (Director), Catherine MacKinnon (DI), Chris Dodd (Performer), ULTRASOUND, 2016. It is important for the ASL coach to check in with the director from the outset regarding artistic vison and to maintain ongoing communication with the director around interpretation of sections of the play as they arise.

- The ASL coach provides feedback on proper ASL grammar, dialectical variation, sign language use depending on educational background of the characters portrayed in the production, interpretation from script based on intent, artistic delivery, appropriate use of signing space on stage.

- Size of theatre influences the signing space with a larger theatre requiring a larger signing space.

- It is very helpful for the coach to videotape the role being interpreted through the entire play in advance of rehearsals for the actor to review.

- Of utmost importance is to check the ASL dialect long before rehearsals begin.

- ASL interpretations of script should also take place before rehearsals begin.

Vocal Coaching

- A vocal coach can be of assistance to Deaf actors who play a speaking role in a production, with regards to breathing, relaxation, sustained voice usage, and proper projection techniques from the diaphragm. Diction and pronunciation may also be part of the discussion to be determined by the actor, director and include the playwright’s intent regarding the characters’ cultural origins.

Stage Management[3]

- The Stage Manager (SM) is in a position to help navigate anything that happens during rehearsals and the performance run regarding tech or personnel.

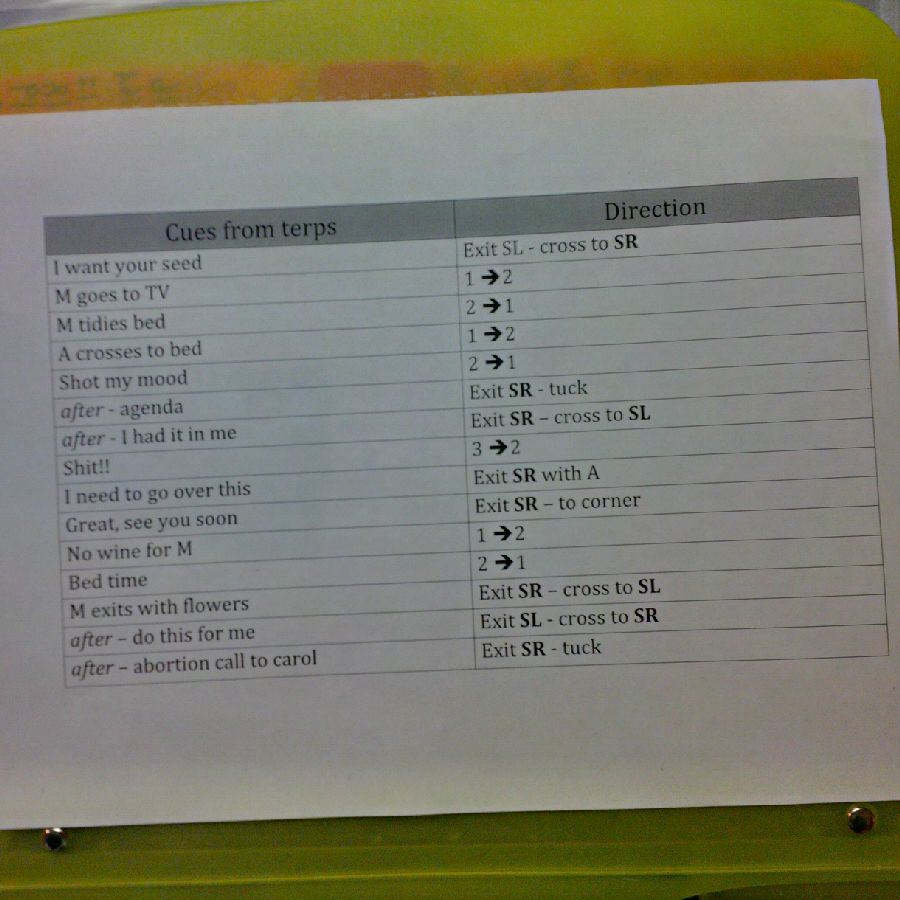

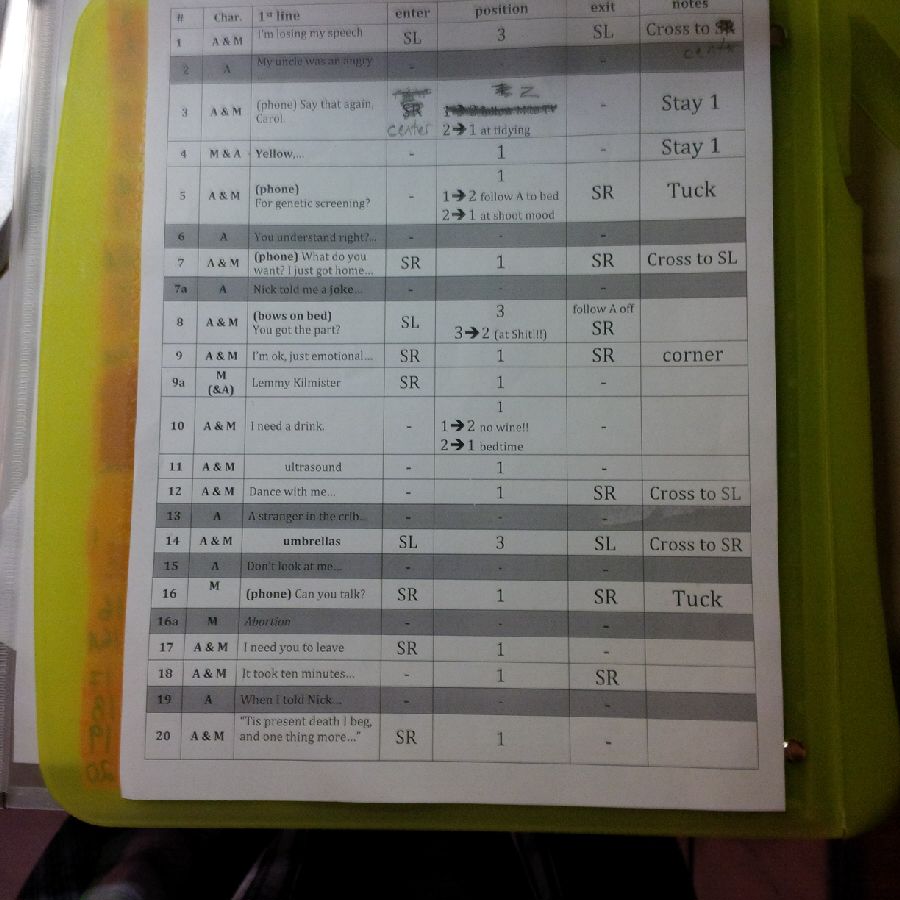

- Blocking – It is important to take detailed notes and establish a baseline for tracking blocking with director / performers in the first week.

- The actors should not rely on the stage manager’s notes, but rather, they should work out their own methodology for tracking their staging, whether it be visual drawings or cheat sheets.

- Scheduling – SMs and Directors should be aware that with interpretation, there will be additional time required. It is important to produce rehearsal schedules that reflect this reality.

- Breaks – Establishing a protocol for the end of breaks so that everyone returns on time (eg. flashing lights so there is a clear visual means to call everyone back together). At the same time, it is everyone’s responsibility to watch their own time.

- As the SM is responsible for communication across the entire team, the SM should take the lead in the room in making sure time for interpretation has taken place for any communication throughout the rehearsals.

- The same is true in technical rehearsals, and doubly important as much of the production team is in the dark, with performers in the light. Small added cues can be added to establish ‘lit’ interpretation stations in the house or onstage to assist with facilitating interpretation during the tech period.

-

Photo Credit: Dahlia Katz. Stage Manager, Sandi Becker and Director, Marjorie Chan with actors and interpreters in rehearsal. The SM may find it more challenging to know the mood of the room if s/he doesn’t know sign language well and/or is not a part of the Deaf community. The SM may find it difficult to pick up signed “rumblings” in the room. The Deaf Community Consultant and/or Cross-Cultural Consultant can be enormously helpful in this regard and can report to the SM any relational issues that may arise in order to properly manage things.

- It is important for Deaf and hearing members to all be given information at the same time. This is a particularly sensitive subject for Deaf community members as they may feel that they have been “the last to know” at other times in their life.

- Ensure all language is familiar–because of lack of access and less exposure, some theatrical terminology (eg. “fight call”) may need to be clarified. It is important to allow time during rehearsals to provide clarification, as required.

- In rehearsals, ensure that individuals who aren’t present all the time and don’t have familiarity communicating with Deaf individuals, are made aware that they should talk directly to the Deaf actors and not to the interpreters.

- Another communication tip is to take turns speaking one at a time – talking all at once makes it impossible to interpret; eye contact is critical before you speak, and if an interpreter is present, look at who you are speaking to, not at the interpreter.

Rehearsals

- At times, rehearsals can have MANY people in the room. Allocate twice as much time during rehearsals to allow for effective communication and interpretation.

- It is visually exhausting for a Deaf performer to watch an interpreter all day during intense rehearsals. Instead of a few long breaks in the day, Deaf actors will benefit from more frequent shorter breaks.

- During rehearsals and tech week one person should talk at a time. There should not be overlap since interpreters cannot interpret more than one message at a time.

- Communication should be at a normal pace – not too fast or too slow to allow for interpretation.

- Scripts must be given to DI’s, Interpreters and Deaf actors immediately. They need time to interpret into ASL when changes are made. There are sensitivities related to being left out of new knowledge as it is typical for members of the Deaf community historically and so sensitivity to this issue is deeply valued. Also, the Deaf community strongly values the collective so if all Deaf actors don’t have the same information then it disrupts their collective way of being and sharing information with each other. [4]

- Deaf actors can markup their scripts highlighting the ASL lines so they can quickly scan the script to find their specific ASL lines.

- The Director and ASL interpreters should work out staging language before rehearsals begin as well as the overall aesthetic approach. For example, a very general comment from a Director can be a deliberate choice on the Director’s part in order to allow the actor to make a choice. This approach may be antithetical to Deaf culture. Be direct about what you want when communicating with Deaf actors. Spoken English tends to be more general to specific. ASL gets to the point right away.

- Planning – Directors should plan a balanced mix of table work (script discussion) with actual staging time pending on the need of the actors (for example, a Deaf actor may prefer the physicality of staging/exploration but another Deaf actor may wish the entire scene to be discussed before jumping in). Adjust for additional time in rehearsals for these considerations.

- When giving directions to actors during rehearsals, specify which actor the comments are directed to since the interpreters won’t intuitively know who the director is referring to.

- Music stands should be available for actors

- When working with a changing text, it can be helpful to project new dialogue so that there is a common visual reference. This can be accomplished with an office projector.

- During Tech week, actors are left on their own quite a bit and it feels different in the rehearsal hall because it happens in the dark. This can be isolating for all actors but may be felt even more acutely for Deaf actors.

- One of the most powerful moments during the rehearsal period for ULTRASOUND was when we realized that the DI strategy needed adjustment in order to keep up with the timing of the actors. The problem was a large lag time from the actor’s line delivery, to the hearing interpreter’s interpretation (seated in the house seats facing the stage) and then the DI’s interpretation on stage from that. It was difficult for the DI to know when to deliver a line and which one was her line. All crew brainstormed, simultaneously huddled with each other in their own fields of specialization – tech support huddled to consider prompters, the cultural consultant, interpreters and DATT project manager huddled with the Deaf actors, and the production team huddled and we all came up with potential solutions sharing them with one another until we experimented and decided on the most effective solution for this performance – use of two interpreters in the house seats with delineated roles so the DI would know when her character was about to speak and what she needed to interpret. The important learning from this and the gratifying result, was to see the power of the collective in seeking an optimal solution.

[1] Tips from Nina Okens, Costume Designer, ULTRASOUND

[2] Surtitling tips from Trevor Schwellnus and Sally Roberts; lighting tips from Trevor Schwellnus

[3] Tips from interview with Sandy Becker

[4] Tip from actor, Elizabeth Morris